“You can’t connect the dots looking forward; you can only connect them looking backwards. So you have to trust that the dots will somehow connect in your future. You have to trust in something – your gut, destiny, life, karma, whatever.” – Steve Jobs (2011)

It was the one question we could be sure would be asked.

Every.

Time.

And, it changed my perspective on the whole game…

Scene: It was a Spring day, 1990. 730 am. Pre-market open equity option traders meeting. O’Connor & Associates, 7th Floor, 141 W. Jackson Blvd., Chicago. Arguably, the world’s leading proprietary derivatives trading firm of the era.

My first of a few years’ worth of these meetings. A neophyte member of the fledgling fundamental research team sitting amongst new colleagues whose first language was either Greek, or 1’s and 0’s. Clay Struve – the Chief Brain of the operation and legandary conjugator of FX crossrates through the haze of the previous nights’ yard of beer – plus a few other partners and senior traders – sat at the big boy table. The lower ranking players lined the walls and crowded the doorway off the main upstairs trading floor.

Joe Scoby – who later went on to lead UBS O’Connor’s successful quantitative hedge fund efforts and who now plays a similar role at ex-Citadel partner, Alec Litowitz’s, Magnetar Capital – was dangling his legs off the file cabinet over there. Daniel Coleman – who later went on to be CEO of the merged Knight Capital and GETCO operations, and then helmed the sale of that combined firm to Virtu – was among another subgroup of 20-something punks holding up the whiteboard over there. Other notables peppered this disheveled crew clad in jeans and T-shirts that went on to play leading, innovative roles throughout the industry. Suffice to say, it was an unusual room overlooking an unusual place with an unusual collection of souls…

With this scene as context, the principal question us analysts were expected to answer for the traders on this morning and every morning thereafter was always: What’s the next catalyst?

In other words, what causes volatility?

Now, this question was usually directed in such a way as to put a company – and its stock – at the center of the target. And, the answer typically corresponded to a taxonomy of event categories – like earnings or FDA meetings or industry conferences or an 8-K filing – which are still handled in a similar manner today, except perhaps a lot faster. However, at its essence, the real question was:

What is the next data point that will make the wiggly line move? And, ideally, by how much?

Relative to my peers at other, more traditional, asset management firms and sell-side shops, this wasn’t as much fundamental research as it was an interpretation of the flow of data. In fact, it was both – and for that reason it was more like advanced fundamental research. No one else was doing it…

Longer story shorter, analysts were highly motivated to discover and organize the scatterplot of future catalysts for their assigned groups of “wiggly lines.” And, in my case, it lead to an obsession beginning in 1992 that culminated in a patent to gamify – via visual language – a dashboard dedicated to the assembly and display of catalytic data…

This factoid brings us (finally) to the crux of the point for this post: Each wiggly line – whether it be a stock or index or commodity or spread – sits at the center of a taxonomy of primary, secondary and tertiary catalysts. In the case of company-specific securities like stocks and bonds (and their derivatives), primary = company, secondary = group or sector, and tertiary = market.

This is where we get to the newest Fed Chair, Jerome Powell, who is the most powerful source of primary catalysts for global markets and tertiary catalysts for individual US companies in the entire world. He has the power to make everything move…

I had hoped that, after the long, 30+ year interventionist legacy of the Greenspan-Bernanke-Yellen triumvirate, Mr. Powell would be more respectful of the real price discovery that results from a freer, more independent and less-centrally-influenced markets. (You know, the ones regular folk always insist we actually have – relative to places like China – on the nightly news and at political rallies!)

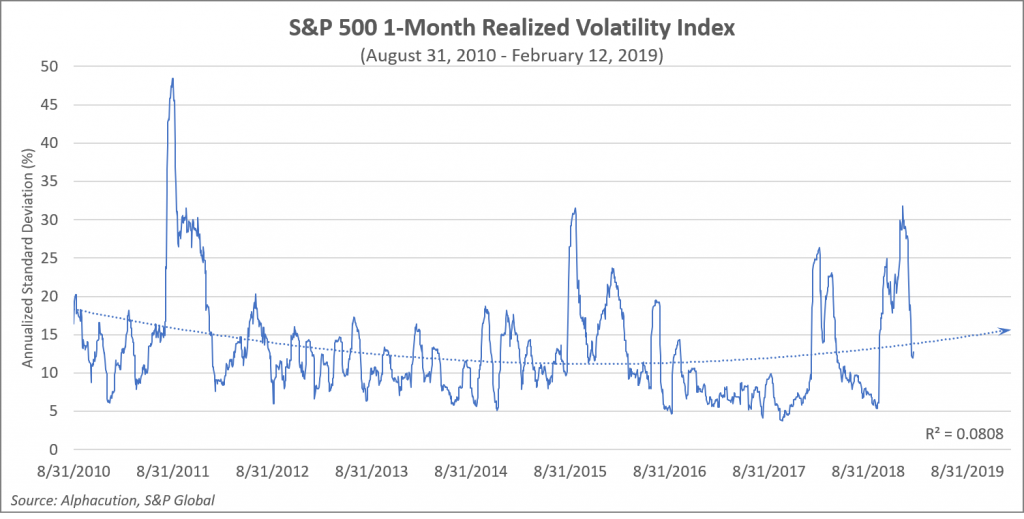

As a refresher, here’s a look at the last 2,123 trading days (8.42 years) as represented by 1-month realized volatility of the S&P500 Index, see below: (Note – Realized volatility measures the annualized standard deviation in the daily price return of an underlying security over a given period, in this case over 1 month’s worth of trading days – typically, 21 days.)

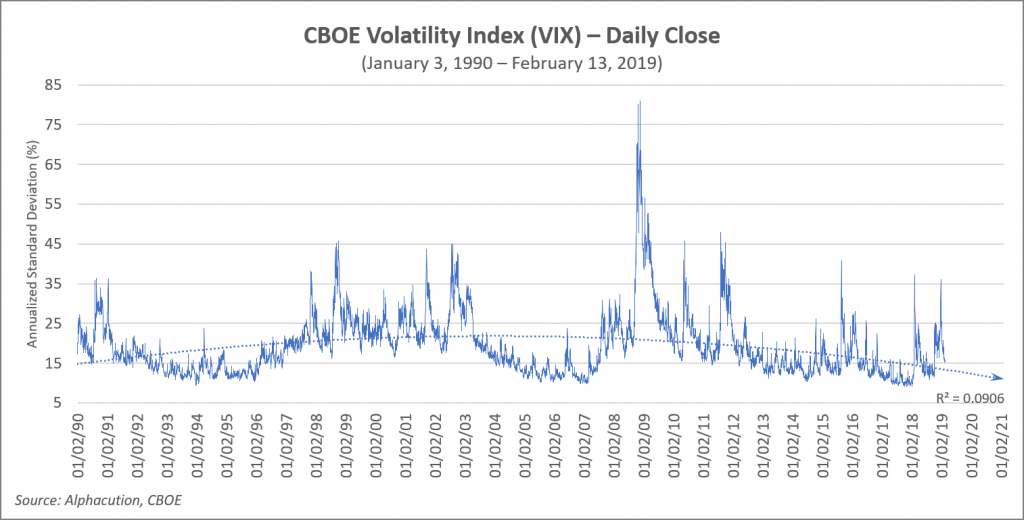

This is a subset of the time period for the full 7,337 trading days to date – or, 29.1 years – of CBOE Volatility Index (VIX) data that begins January 3, 1990, as shown below:

In both cases, what we want to influence here is a familiarity with the shapes of the various historical volatility time series data.

Why?

If you have been paying close attention at home – reading some of our storytelling around the factors that ultimately drive the profitability of market makers, HFTs and other prop shops closest to the center of our market structure ecosystem – then you already know that the granddaddy factor of them all is volatility. And that, my friends, makes the question – What’s the next catalyst? – among the most important of them all…

Consider: For the full 7,337-day VIX time series above, there are only 68 days (or, 0.9%) when VIX closes below 10% and only 56 days (or, 0.8%) when it closes above 50%. Furthermore, 89.3% of the days closing above 50% occur in 2008, when we know for sure that catalyst(s) related to the collapse of Lehman Brothers and the various contagion of the global financial crisis (GFC) occur. However, 86.8% of the days when VIX closes below 10% occur in late 2017 and early 2018. Here we have no single or group of discrete catalysts to explain the lack of volatility – which happened to be about the same time our President is toying out loud with the idea of using nuclear weapons on North Korea (and other mayhem), and the end of the tenure of Fed Chair Yellen. No biggee. Nothin’ to see here.

Hold that thought…

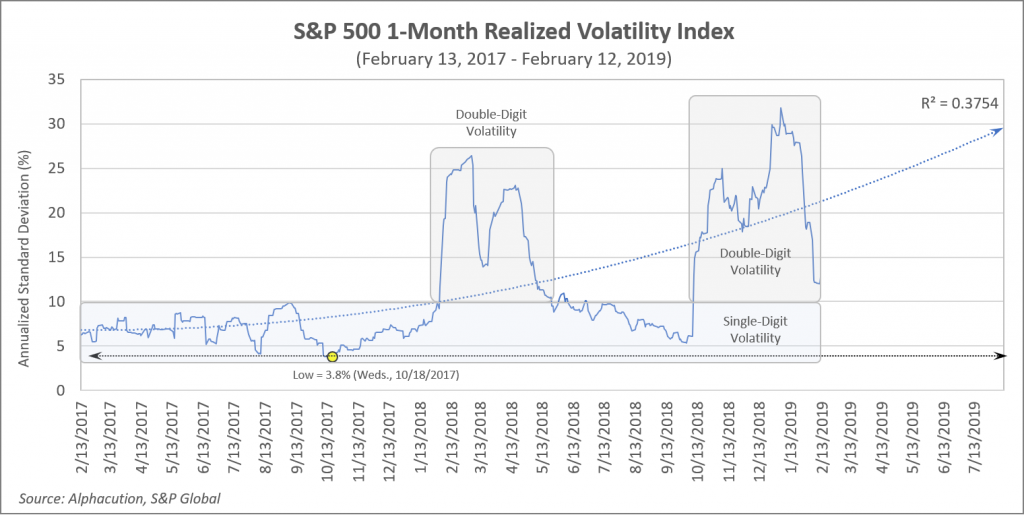

Now, let’s return to recent volatility with the last 2 years of S&P 500 1-month realized vol. In both cases where we have double-digit realized volatility, we are in the new Powell-led regime of gradually normalizing interest rates, which in our taxonomy is a series of tertiary market catalysts for US equities and related securities, see below:

Bottom line: Volatility is not a bad thing. It is actually a barometer of market health. Volatility that is too low can be just as destructive as volatility that is too high. Market actors that essentially serve to lubricate liquidity pools tend to “dry up” during extended periods of excessively low volatility, such as that seen in late 2017 (when the “powers that be” may have wanted to counterbalance an unusually combustible political environment).

In early 2018, with Chair Powell transitioning into his new role, it appeared that the Greenspan era that began in August 1987 and continued by 2 predecessors may have finally come to an end with the welcomed spike in volatility – and the ongoing sense of finally normalizing interest rates. However, this latest spike in volatility that made 2018 the worst in 10 for stocks seems to have pumped the brakes on additional rate increases in 2019.

The Fed Chair – whomever he or she may be – holds the greatest power on the face of the planet to influence markets, and market volatility. With a convergence of factors – namely, rise in portion of pooled structures (like ETFs), decline in portion of new equities, and declining willingness by our democratic central planners to allow “free markets” to exhibit what might actually be a healthier level of risk – our new Fed Chair’s role as Mr. Volatility may have been short lived.

Still, it’s always worth keeping our eyes out for the next catalyst…