On Monday, 3 October, ING Group – formerly the Netherlands’ largest lender and one of the world’s largest financial conglomerates – announced plans to cut 7,000 jobs from its ranks of about 52,000 in order to invest in digital platforms that are expected to generate annual savings of 900 million euros ($1 billion) by 2021. Beyond this, what is fascinating about ING is the rare glimpse it gives us into the post-global financial crisis (GFC) dismantling of one of the world’s financial behemoths. We have few other case studies – although, oddly enough, ABN Amro does come to mind – where we see the persistent “reverse-conglomeration” of a large and global financial services powerhouse.

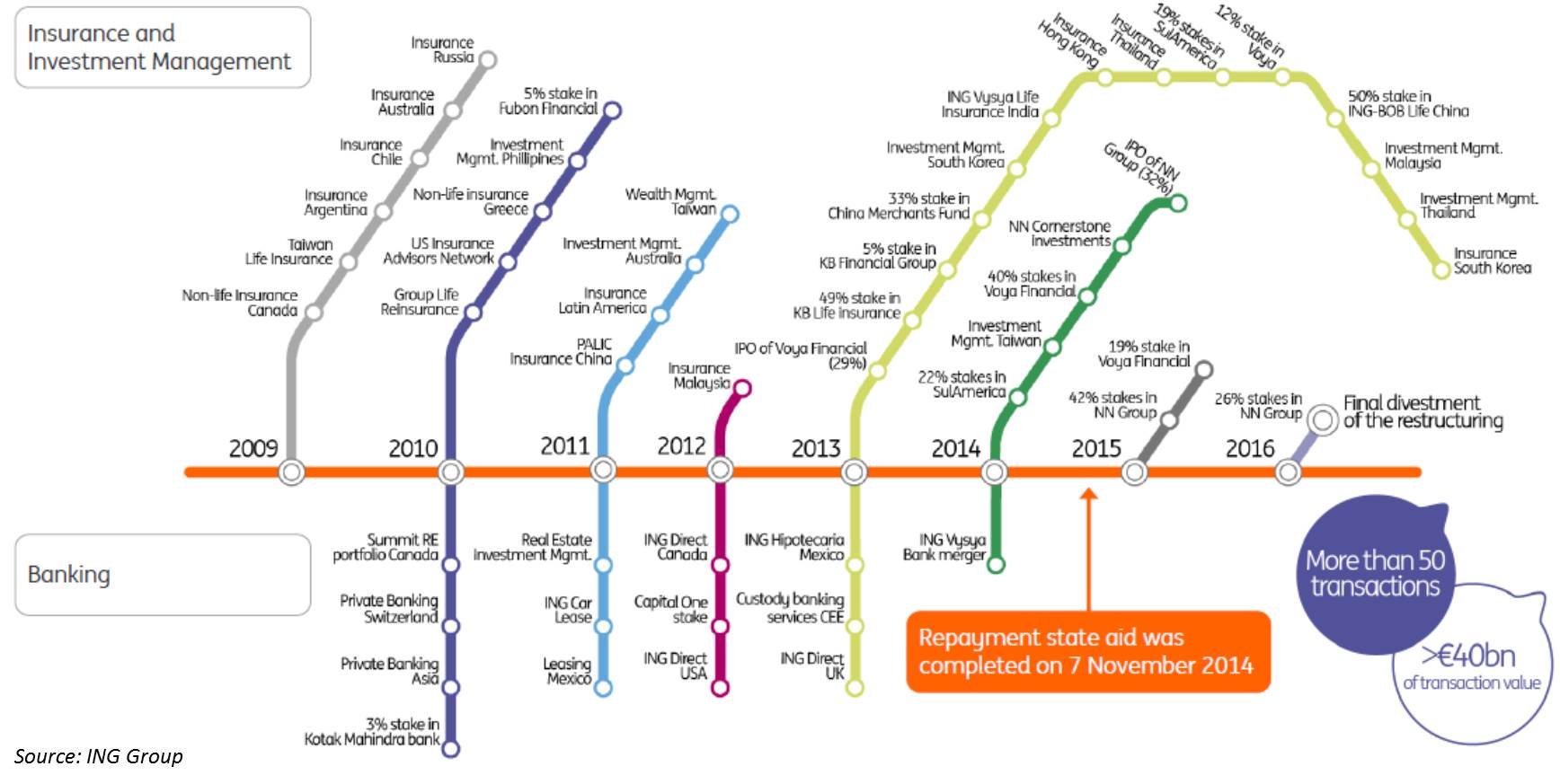

As a stipulation of the Dutch state-funded capital infusion in the wake of the events surrounding the GFC in 2008-2009, ING Group was essentially forced to sell off numerous businesses in order to maintain or exceed minimum capital ratios. The chart below details the timeline and more than 50 divestitures that have occurred since the GFC.

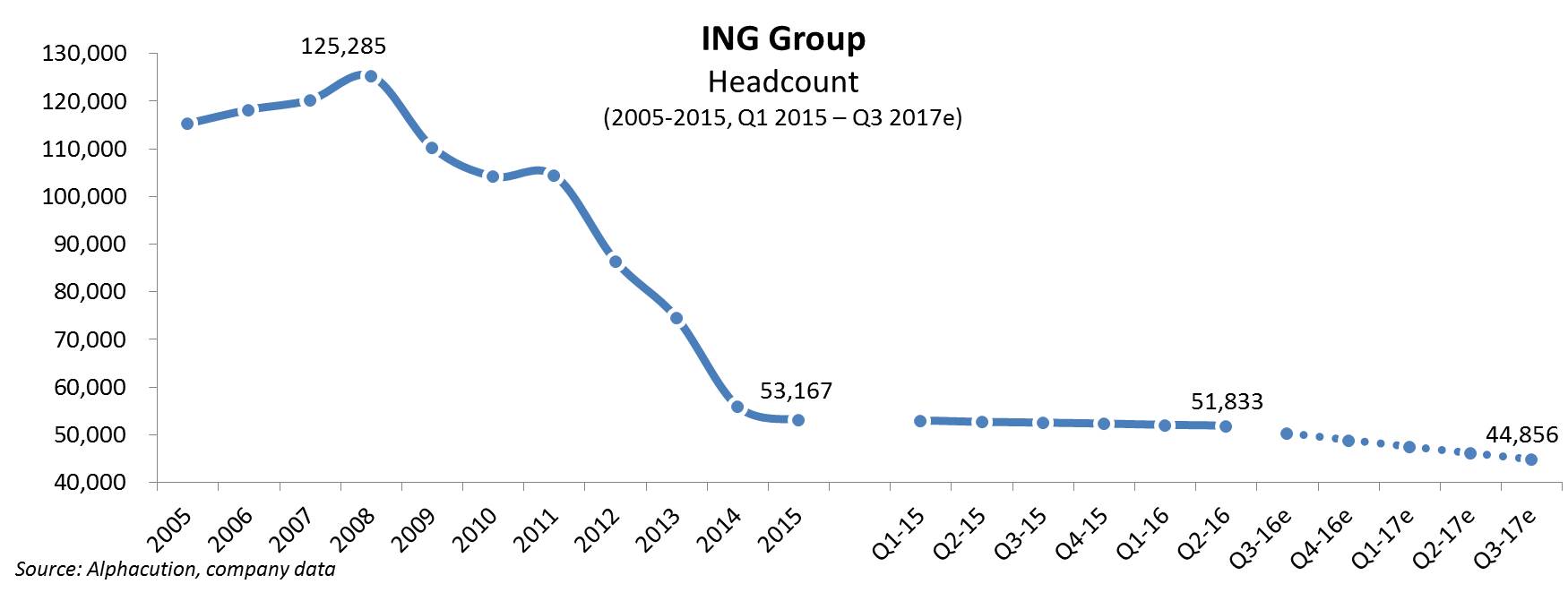

Here is what this transformation looks like from a headcount perspective – which gives us a peek into why the recent announcement for further reductions is so fascinating:

First, it is notable that from the headcount peak at the end of 2008 and beginning of the GFC (>125,000), it took about 7 years to complete a divestiture program that yielded more than 50 transactions and a headcount reduction of ~72,000 (full-time equivalent) employees. After all this, and while staffing has continued to trickle slowly downward for the past several quarters, a program and strategy to consolidate onto a digital platform is just now being promoted. By our estimation, average quarterly reductions in headcount of -0.5% (over the past 6 quarters) will need to be amped up to reductions of -3.0% per quarter in order to achieve the aggregate reductions of 7,000 employees over the course of the next year.

Here are a couple major takeaways: 1) It always amazes how long it takes for large organizations to change – and, in this case, simply to prepare to change; 2) given the political season, this case study provides somewhat of a road map for other large and complex financial intermediaries, should proposals to address “too big to fail” come to fruition, and 3) it seems a little late to the game to just be starting a digital transformation program. Certainly, this last one falls under the umbrella of “better late than never,” but it really is noteworthy how slowly some enterprises are to move into action. On the other hand, this could be an efficient and optimal pace – it’s just the scale that makes it seem so slow…